Following the winter power crisis that swept through Texas and forced my family to flee my powerless, waterless home for four nights, I have been thinking a lot about tail risks.

I would say any good immersive designer needs to think about tail risks, but really any good business owner needs to consider them. You offer a thing to other people, you invite tail risks.

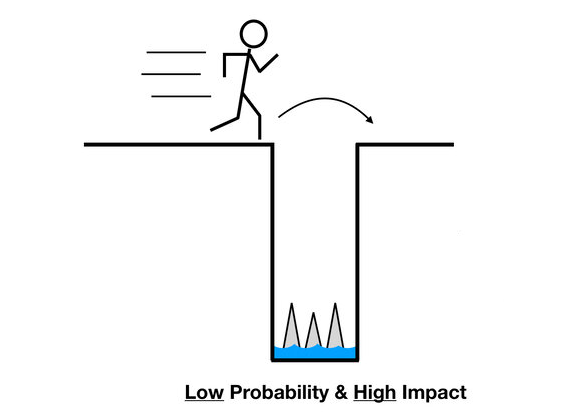

A tail risk is a term I’m co-opting from finance. Event probability follows a bell curve, some events being extremely probable to happen for your guests, but along the “long tail” of the curve lie events that are unlikely to happen. But still possible. The tails pose a risk.

Since the first meetings of Strange Bird Immersive, our creative team has been obsessed with tail risks. We’ve protected against it in the design phase, and when issues arise in the execution of the design, as they inevitably do, we prep to mitigate the negative risks so they have minimal impact.

Our creative partner Nathan Walton, lesser known to the public than Cameron and I but no less essential, taught me a great deal about tail risks. He’s cautious. “Sure, it’s unlikely to go wrong, but when it does go wrong, just how bad is it? Visualize how bad it is,” he says. If it’s bad…we need a re-design or a fail-safe Plan B. Nathan’s a risk exposure expert. I love him for this (and many other reasons).

We learned this lesson the hard way back in August. Thanks to spotty internet, we took the risk to have Professor Hazard in The Strange Secret of Mr. Adrian Rook host via LTE hotspot rather than deploy the recorded video/understudy solution (our Plan B). We tested the connection ahead of time, and it seemed good enough. If we discovered it failed with the first group that night, we could then deploy Plan B. Trouble was, the first group he hosted was a bunch of critics from four different media outlets, and…his connection failed.

High impact, indeed! I didn’t properly visualize. We’re internet paranoid now, but we can never fix that group’s experience, and that’s not cool.

There are two types of tail risks to consider: experiential and existential. Let’s dive in.

experiential tail risk

An experiential tail risk is where something really unlikely happens, and it impacts the guest experience. Their level of fun goes down.

Every business has some tail risk—like, how bad is it when a customer doesn’t like the service? When an employee doesn’t show up? When we run out of sweet potato fries? These are common.

But the more you invite your guests to act, the more risk you take on. Immersive entertainment, especially escape rooms, are all about inviting you to act. Humans are wild, original creatures. There’s going to be a wider range of behavior on display, say, then you’ll see running a movie theatre, so the list of tail risks is simply much longer.

And if you run a thing over 500 hundred times, you’re likely to see that 1% chance occurrence show up 5 times. The best designers will plan for it.

What happens when the warded lock fails? We’ve got spares.

What happens when the actor forgets this prop? Here’s the best improv! (Oh, have I seen some lovely improvs. Our company is smart).

What happens when that object isn’t precisely where it needs to be to trigger the thing? Do we run a hint saying “Please nudge the MacGuffin two centimeters to your right?” NO! We have software that allows us to mark it as present without the players ever being bothered.

What happens when the image recognition software fails? The game master can hit the trigger. What if the server fails? Well, there’s a secret physical pull knob that never fails.

What happens when a psychic-guest randomly guesses the word lock? We let them play! Puzzle flow jumps—where players unlock something out of the intended order—can happen, whether from a bad reset or a guest’s supernatural ability. We have a strict list of only two instances where we interrupt a team because of a puzzle flow jump, and that’s when the impact of interrupting them is less than the impact of breaking the game too wide open. In every other case, we know our puzzle flow well enough to know it’s okay to let them jump and play it out.

Or how about when the magic fails? In Strange Secret of Mr. Adrian Rook, Madame Daphne has a Plan B and a Plan C for her magic. And yep, 150 teams in, I’ve deployed them both.

Point is: we do what we can to impact the experience as little as possible and move forward.

Really, I think the heart of escape room design is about designing for tail risks. You want to keep every team within the boundary of the experience while inviting them to explore for themselves. Physical parts + creatively engaged humans = a tricky thing.

Hints mitigate tail risks

Hints (not to be confused with clues) are the assistance we variably give teams when stuck on a puzzle and unable to advance. Some teams need zero hints. Some teams need eight. (We average about one—design for the fewest hints possible. Trust me. Hints feel like a defeat, no matter how immersive the delivery.)

Hints allow us to handle the unexpected “tail risk” behaviors. Hints keep every team, from the 70 year-old ladies to the enthusiasts who can’t search to save their lives, on the right track. We have a stock set of hints, but it’s essential to have a hint mechanism that allows you to tailor your message to a team. There’ll always be, “One time the team did this…” and you’ll be glad you were able to redirect them with a custom message.

THE TAIL RISK TOOLKIT

Here’s a look at the tail-risk toolkit.

- Design. This is the first stage and the best way to mitigate tail risks. Imagine guests of all ages and sizes and behaviors. You don’t put a knife in your kitchen-themed game, do you? Physical puzzles especially demand good design: what do you do with that team of two where neither can physically crawl through your crawl tunnel? Or a team where everyone is too short for the input (there’s a hard reason we can’t host a team of 10 year olds, y’all).

- Spares and repairs. Things break, especially after hundreds of over-eager hands have handled them. We have a policy of “don’t just replace, improve!” whenever something fails, and that approach has shortened our list of things that are vulnerable to fixing. Nonetheless, light bulbs still go out, paper gets torn. When X fails, how do you carry on for the next team arriving in an hour? Be ready. Often with glue or a ladder or a duplicate from the spares shelf.

- Responsive repair technician. When the fix goes beyond the game master’s capabilities, you need a repair guru that understands the thing on stand-by. Otherwise, you risk delivering a broken game (and nothing gives Strange Bird panic attacks like nixing a puzzle for the next team).

- Electronic Plan B. An automatic electronic trigger may not work. We build software that allows us to trigger events via game master if the automatic trigger fails.

- Manual Plan C. Should all electronics lose their mind, we deploy a physical solution that can never fail.

- Hint and warnings. Useful for redirecting mental attention (hints) or stopping unwanted behavior (warnings). Have the ability to customize these.

- Game-master interruption. We deploy this only when something has gone so wrong that it needs to be brought to the entire team’s attention. Either an object has broken or team behavior has not responded to our text-based “warnings.”

- Customer Service. So many ills can be smoothed over by confident and attentive service.

Prep your toolkit because—trust me—one day you will need it.

Train Employees for Tail Risks

None of these preparations are any good if you don’t train your employees to use them. A good game master should not only be trained explicitly in hint style, but also know what can break, when to interrupt the game, and how to fix it. Perhaps above all else, you should let them know that you can’t prepare them for every issue that will arise. Tell them you trust their judgment. They are authorized to do whatever they deem necessary to preserve the team’s experience.

I wonder if I spend more time training our company in tail risks than in rehearsing scene work. Scene work is easy in comparison! You really should see our training manual…

My favorite interview question for Strange Bird is, “Tell me about a time something went wrong on stage, and how you responded.” If their face doesn’t light up, they’re not going to enjoy working here.

INVESTING IN TAIL RISKS

It’s worth noting that what I’m recommending is expensive. Preparing for tail risks is an investment of time and treasure. It rarely comes up, so from a business perspective, it isn’t always profitable. You have to care about each and every customer’s experience to go on this mad rampage like we do.

Maybe we’re obsessed with tail risks because we’re artists. Maybe we’re a little consistency-cuckoo. But I do know that Strange Bird’s commitment to mitigating tail risks contributes to our high reputation. Games differ team to team, but everyone who’s played The Man From Beyond talks about the same magical experience. Because we don’t let anything derail it.

That’s got to help our bottom line.

THE EXISTENTIAL TAIL RISK

This second category of tail risk is the most important. It’s risk that is about safety. It goes beyond a threat to the guest experience, to a threat to the guest’s life.

There are lots of existential tail risks in escape rooms: what if the power goes out? What if that pneumatic special effect activates with someone standing there? (an example of the kind to design against). What if someone trips over a threshold? Or injuries themselves with their own exuberance?

Here’s a classic existential tail risk for escape rooms: do you lock guests in? Escape rooms have pivoted away from locking guests inside the game, even eschewing the safest option of push-to-exit maglocks. Room Escape Artist freaking grades escape rooms on emergency exits now, and I’m glad they do. It helps incentivize safety.

I’ll confess: in our first installation in 2016, we had a maglock on the parlor door.

Why did we do that? Honestly…? Because everyone else was doing it. It was one of the tropes of the genre.

When it came time to rebuild the parlor in our new location in 2018, we nixed it. We gained absolutely nothing while taking on a serious tail risk. We knew by then that people stay where the action is, and we don’t care if someone leaves to go to the bathroom! If that’s what they need, that’s a good thing!! But most importantly: should something go wrong in the room, would the team think to push the pretty little button beside the door?

I shudder knowing we once risked this.

And then there was the fire in Poland. Remember it. Learn from it. STOP LOCKING EXIT DOORS IN ESCAPE ROOMS. (And thankfully, the industry is doing just that.)

It is extremely unlikely that there will ever be a fire at Strange Bird Immersive. And yet, we have spent tens of thousands of dollars should such an event take place. We have EXIT signs and emergency lights and bonus doors we didn’t want in our architecture so the path to exit the building never exceeded 75 ft. We spent at least $10,000 on a fire spray for our ceilings.

While I’d like to think we would have opted for these safeguards, we were saved from any moral wrestling. We are legally required to have these safeguards in order to receive our official Certificate of Occupancy from the city. While 10% of the hoops we jumped through were bureaucratic bullshit, 90% of those hoops were about not taking on the tail risk of killing people. To be frank, not everyone is willing to invest in that on their own, so they force you to.

That’s what regulations are all about.

THE ASSHATERY OF ERCOT

A failure to invest in a tail risk is why so many of my fellow Texans experienced a tragic week. For those of you out of this particular news loop, for five days last week, power was out for days in millions of homes across Texas, where indoor temperatures plunged to the 30s. The blackouts impacted the whole state, thanks to power plants freezing and 30,000 megawatts going offline. People died.

Texas has an independent power grid, run by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT). It’s notoriously deregulated. Following previous winter blackouts in 2011, recommendations were made to winterize the power plants. The recommendations were not followed.

Yes, it is unlikely that the entire humongous State of Texas would undergo a deep freeze at the same time. But if that did happen, how bad would it be? Visualize!

But wait, I forget, you’re not properly incentivized here, are you, ERCOT?

Preparing for a tail risk requires investment, and if the goal is profitability, it may not be worth it—especially when you have a monopoly over your customers. You can freeze them, displace them, even kill them, but it’s not like you’re going to lose their business. So…why should you…?

Regulations are written in blood.

Ask me how I feel running an escape room company more responsibly than Texas runs its energy grid.

Don’t be ERCOT. Invest in your tail risks. Care about each and every person, even if it’s not profitable.