A little over a year ago, Strange Bird Immersive opened The Strange Secret of Mr. Adrian Rook, a virtual immersive mystery where teams of eight visited six different strange tenants at Strange Bird and uncovered the secret of the missing secretary to the Raven Queen. (It’s closed now—thank you to every guest who joined us.)

We never planned to run a show like this, but the coronavirus had other plans. A one month run turned into eight. Given the intimacy of immersive theatre, we chose to keep The Man From Beyond closed until April 10, when our performers were fully vaccinated. We would otherwise have had zero income for thirteen months—and thirteen rent bills. Strange Secret changed that and changed the spirit of the time, too. Even in the bubbles of our separate spaces, we were connecting with people again.

Looking back on it, Strange Secret reinforced a very important lesson for me: iterate your interactions.

iterating puzzles

A company culture of iteration is one of Strange Bird’s super-powers. We keep tweaking things, until they hit that sweet spot of challenging but surmountable.

It’s a given in the escape room community that you need to test your puzzles. Your puzzles are always harder than you think. You can never fully anticipate how people will respond.

There are many stages of iteration. We go through alpha testing (internal to the team), then beta tests (invited), then previews (public), and then there’s the long tail of being “open” but still watching and tweaking. The first three months of a new experience are very active in iteration, then it settles down at about six months, we’ve found. But The Man From Beyond opened over 4 years ago, and I recently changed the size of a paper clue by 25%, and it’s currently performing better.

We never stop iterating our puzzles.

interactions are puzzles

But what about questions to the players, or calls to engagement—moments that aren’t explicitly puzzles? You should iterate those, too.

People staring blankly at you when you ask a question? Probably this isn’t the response you had in mind. Just like an under-clued puzzle that’s causing frustration, this interaction is broken. So fix it!

Vivian Mae’s Secrets

At the opening to Strange Secret of Mr. Adrian Rook, guests meet Vivian Mae, proprietress of Definitely Not a Speakeasy. She has a collection of secrets customers offer her that she keeps in bottles.

We knew we wanted a “secret-themed” engagement with the audience, so in our initial draft, Vivian Mae opened by asking one guest to share a secret as tribute for entry. Here’s that script:

But I do ask one last task of people who come through my door

Before I pour them a drink,

And that is…share a secret with me.

That’s what a Speakeasy is all about, of course,

Sharing secrets.

So I would ask a secret from someone here,

And in return, I’ll share a secret of my own.

An even trade.

What better way to get to know one another?

Perhaps the sort of thing you wouldn’t post on social media.

But true, nonetheless…?

Who has one?

We wrote, rehearsed, and built the show in about two weeks before getting it in front of a beta audience. (Speed being of the essence in the pandemic.) This engagement went okay in the beta, but I got feedback that opening the show with an engagement so intimate was challenging. When I looked at it, I saw this was the most challenging engagement of the whole show.

So we moved the question to the end of Vivian Mae’s scene, when she has built more trust and has shared examples of other little secrets. We also changed the text to suggest easy secrets, to help coax folks.

Your turn.

Does anyone here have a secret you’d like to share?

It can be a small one.

No need to turn your hair into a feather or anything!

A simple secret will do.

What better way to get to know one another?

Perhaps the sort of thing you wouldn’t post on social media.

But true, nonetheless…?

Something surprising about yourself,

The website you visited earlier today,

Your secret ambition.

Who has a secret?

The engagement again went okay in our next set of previews. I know we had seasoned immersive theatre folks present (always a risk with early testing, that you attract experts), and they often enjoy taking the spotlight.

Then we opened to general audiences.

We didn’t have the option to film our other groups (permission and all that!), so we asked each performer to report back to us on how groups were engaging. Two public shows in, and ten groups later, Amanda Marie Parker, playing Vivian Mae, was reporting that 20% of groups offered a secret, and while it often made for a very memorable moment for that group, the other 80% of groups stared awkwardly at her.

That’s way too many groups. And not fun for our actress, either. Interactions shouldn’t be like pulling teeth. I’d have changed that interaction if it failed for 1 out of 5 groups. 4 out of 5 was insanely broken.

Why it didn’t work

I have some theories.

The format of the show wasn’t kind to this engagement. There’s a group of 7 other people—some of whom you may not know—watching. Due to the virtual format, every engagement in Strange Secret felt like stepping into a spotlight more than we’d like. (Speaking over Zoom feels like that in general, which is really problematic). It’s possible such a question would work better in a one-on-one interaction between character and player, so that the player doesn’t feel the pressure to entertain their friends and can stay fully anonymous, too. I also think in-person this may have worked better. Everyone hanging out on their feet has a more casual feel than the performative Zoom boxes.

I’d also categorize this level of question as “hard”—it requires on-the-spot storytelling. You have to dig deep into your personal history. People probably have more dark secrets than fun secrets, and those are much harder to share. I really should have tested this question better—I don’t really have one to share myself. That alone should have told me something.

Vivian Mae also opens the show. By the time groups reach Madame Daphne (the fifth character), they are more comfortable engaging. Starting with a hard-mode engagement turns people off before things even get going. Given that we couldn’t move her place in the show order, we needed a softball interaction.

EASIER ENGAGEMENTS

So in the few days between performances, we rewrote a chunk of Vivian Mae. From our experience, softball engagements are more “yes/no” or easy personal recall. Third Rail Projects builds their engagements on yes/no and easy personal recall—the kinds of questions where you can answer without having to think about it. “How old were you when you first fell in love?” is approachable. And impactful.

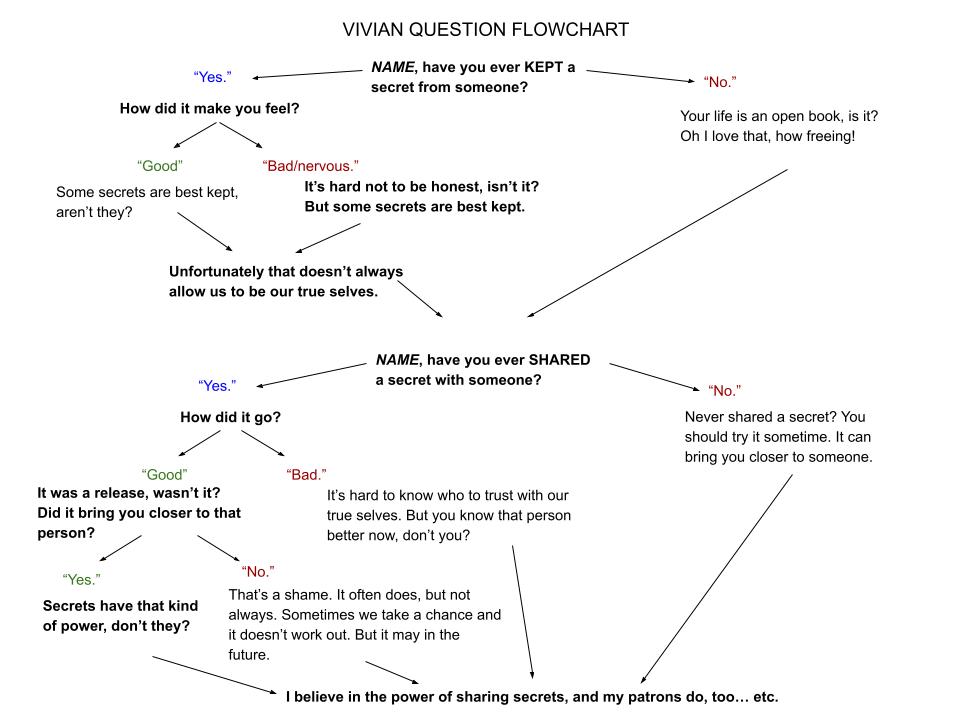

To get that softball engagement, we turned a simple script for our actor into a much more complicated one. The crux of it was two questions:

NAME, have you ever kept a secret from someone? [She engages with them.]

NAME, have you ever shared a secret with someone? [She engages with them.]

Note how now she cold-calls individuals with these questions, looking for someone she deems as present. While we eschew cold-calling in The Man From Beyond, we discovered that Zoom needs something different. Cold-calling allows for smoother interaction in the hyper-self-conscious format, so we changed up our house rules. We still wouldn’t cold-call on a more complex engagement, but for something approachable, we would do it.

Together with Amanda, we created a flowchart for how the conversation in this section would go.

We wrote and rehearsed this change in between performances. And then? We asked her to debut the change with a critic from The New York Times.

It worked. This version became canon. And for extra bonus points, it’s a better engagement from a thematic point-of-view, too, as our hero character must choose whether to keep his secret or not.

Note that we rewrote the interaction twice. Sometimes you have to keep tweaking until you hit the sweet spot. (Puzzle still too hard? Sorry, yes, you do need to add yet more clue trail. It’s not as obvious as it feels, I promise.)

Empower your performers

None of this would have been possible if Amanda hadn’t spoken up. At our end of year party, she earned the “Bravest Performance” award, because it takes courage to speak up to the writers and say, “Your script isn’t working.”

Too often I witness powerless game masters or performers who feel stuck. They can’t fix it themselves, they’re not allowed, and reporting it to their boss (the writer/designer) often won’t change anything either. Or worse, they worry about their job security if they do report it.

I am proud not just of Amanda, but that Strange Bird has created an atmosphere where egos are not at stake. To create experiences that work, you need to acknowledge what is failing—and fix it. And if you are here for the ego trip? In the long run, fixing things will set you up for greater praise anyway. Just saying.

Interactive scripts need more work-shopping than traditional scripts. Like with puzzles, you need lots of players engaging to get a body of knowledge on whether something works or not. Test, watch, iterate, repeat.

The right questions

Here’s another example of an iterated interaction. When we first opened The Man From Beyond, in a moment of heightened tension, Madame Daphne asks the team,

“Can you keep a secret?”

About 80% of teams would concur—great. But 20% would crack some joke, “Well, Susy sure can’t, she’s such a gossip!” etc. Ha. Ha.

Again, we have a group format, which can inspire wanna-be comedians. Maybe if this question were asked in a one-on-one, it’d perform better.

Jokes were the last thing we wanted in this moment, so we changed the question to:

“I will need you to keep a secret. Will you please do this for me?“

The comedians disappeared.

This question makes it a personal ask from the character. Everyone likes Daphne, even if they don’t trust her, and she now receives only sincere assent with this question.

Simple change, big impact.

Iteration is life

At the Reality Escape Convention, I heard the question pop up, “So when do you stop testing? I said, “Never.”

People are creative. The more people engage, the more you learn, the more you can refine your interactions, so that every guest has the best experience. If you’re in the business of interaction, whether that’s immersive theatre or immersive gaming or maybe both, iteration is your ticket to a golden experience.

Every part of your experience can be played with. Guests looking bored at the beginning? Iterate your game master introduction. Have a rule that’s being ignored? Iterate the presentation of the rule, or the wording. From the kinds of emails we send to the arrival time for guests, from the map to our location to the losing sequence, we’ve played with all of these things. Play around until you find what works.

I’m dissuaded from making pop-up experiences myself, because I know that it takes time to get golden. But even with a limited run you can iterate, if a better experience is something you value (rather than say, sheer experimentation, which is a viable value). Ask your performers to report back to you, and be ready to make quick changes.

You need to have a company culture of iteration.

And it usually doesn’t require a major rewrite. Quite often a tiny tweak will do wonders. So let’s tweak it out!

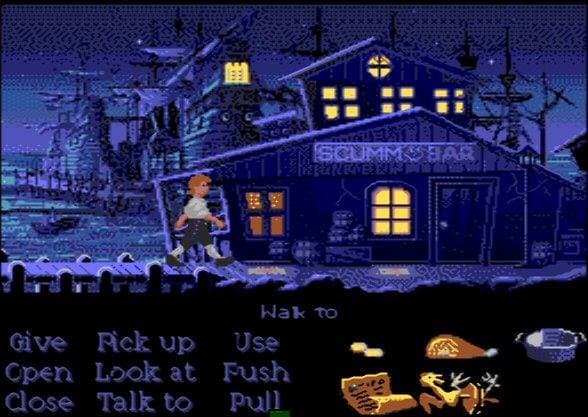

Bonus photos

You made it to the end of the post—congratulations! I know, I do go on. As a reward, here are some fun behind-the-scenes, zoomed-in and zoomed-out photos from The Strange Secret of Mr. Adrian Rook.

Zoom magic is a bit of a mess!