This is gonna be a long one, but an important one, so strap in.

It’s time to tackle escape rooms. I love them. Even when they have no story to tell, even when the set is an office, even when the clue-structure has gone AWOL, I love them. They get me off my butt doing something I’ve never done before.

I’ve made vows to immersive theatre, but a piece of my heart is with escape rooms. Everything Strange Bird Immersive will produce will be immersive theatre, but not everything we create will be an escape room. But our first outing, The Man From Beyond, belongs to both worlds, so today I want to look at the relationship between escape rooms and immersive theatre, and see what it takes for a production to be both.

Think of immersive theatre and escape rooms as siblings. They have more in common where it counts than they have differences. Both industries invite customers to take action inside a designed world. Both invite grown adults to play like kids again. Both use the buzzword “immersive” to sell the experience—and want to deliver on that, too. Together, we make up the new landscape of experiential entertainment.

But escape rooms own a LOT MORE LAND, guys.

Holy crap.

Immersive theatre creators, take note. Escape rooms have already achieved what we can only hope to do in the next ten years. They are the ones mapping the frontiers of what immersive entertainment can be. Like immersive theatre, escape games vary widely in budget and quality, but unlike immersive theatre, people outside of NYC and LA have actually heard of them, and some have even played them. Oh, and did I mention that they easily operate 15-30 times a week, make decent money as for-profit companies when well-managed, and run for years?

Granted, we have different end goals: one wants to give people a fun night of puzzling and the other, well, let’s just say that they never get asked by critics if they consider their work “art” or not. And yes, this may be a novelty bubble, and escape rooms may go the way of laser tag.

But holy crap.

what’s an escape room?

Escape rooms are much easier to define than immersive theatre—although they may not involve escaping, nor do they necessarily happen in a room.

An “escape-the-room” game puts a small team in a room (or series of rooms) and requires them to solve a series of puzzles/challenges/tasks in order to achieve their goal. They have the following features:

- It’s on a deadline: an in-room clock counts down from 60 minutes. When time’s up, you lose.

- It’s hard to do: to win, teams must complete 100% of the puzzles in the game. Puzzles range from complex ciphers involving a Welsh dictionary to rotating bicycle pedals attached to the wall to see what happens.

- It’s important: most often the player objective is to escape the locked room, but sometimes teams need to steal a painting, find evidence of a murder, banish a ghost, etc.

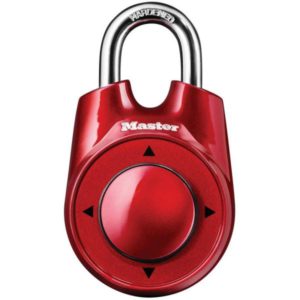

Those of you trained in the Meisner acting technique may recognize these three characteristics as essential to the Independent Activity exercise. When you’re doing something on a deadline and it’s hard and it’s important, you have the key ingredients of drama. And that’s what escape rooms deliver: a dramatic, adrenaline-pumping experience where everything is heightened. Honestly, I go a little crazy under these conditions and inevitably end up in a shouting match with a directional lock. GREAT DRAMA.

Escape rooms may have started for puzzle people, by puzzle people, but they’ve rapidly grown into much more than that. They are an art form.

But can ESCAPE ROOMS be immersive theatre?

Absolutely. I include the escape room in my list of structures that immersive theatre creators work with. But even they are opting more often for sandboxes or dark rides than the more popular escape rooms, and escape room creators in their turn are just beginning to realize that, like it or not, they need the theatrical arts (at the very least, they need to consider sound, light, props and set design).

Despite the commonalities, it’s rare to find an immersive theatre escape room. Remember that tiny purple sliver in the Venn diagram? That’s tiny for a reason other than “we’re not interested in what the other one is doing.” An immersive theatre escape room is super-hard to do. Why? The generic requirements of immersive theatre (specifically: immersion and storytelling) conflict with the mechanics of the game. Boom. My thesis.

For those of you new to the genre, a typical escape room has an employee greet you at the door. He explains what an escape room is, assuages your fears, collects your waivers, and sometimes reads a story or plays a video that kicks off your game. He is not an actor. He then leaves the team alone in the game. With help from cameras and mics, a remote observer provides the team with hints and supervision.

But a few of these games go for something with more flair and involve actors, either outside or inside the room. This is where things start looking like immersive theatre.

To the best of my knowledge, there are only two games in the United States that advertise themselves as both an escape room and immersive theatre: Paradiso (New York City) and my work, The Man From Beyond: Houdini Séance Escape Room (Houston). You can safely assume the creators had the genre in mind when designing the experience and that those who know immersive theatre won’t leave disappointed.

I’m not certain why other games with actors aren’t marketing themselves similarly. Perhaps they’ve never heard of “immersive theatre,” or perhaps they know they’re light on story and don’t want to set up false expectations for anything more than a game. In Scott Nicholson’s survey of escape rooms in 2015 (ancient history for escape rooms, but this trend hasn’t changed much), he reported that 10% of games involved an actor. So actor-games are hard to find, but there are many more escape rooms with actors out there than the 2 who claim the immersive-theatre mantle.

So what does it take for an escape room with an actor to be immersive theatre?

Let’s look at the criteria that need to be met for immersive theatre…

Rule #2: the audience is active

I’ll start with Rule #2 because this is where escape room SHINE. Everyone is active in an escape room, on their feet exploring, observing, twisting, using their eyes, ears, hands, knees. This is what they came here to do.

Escape rooms do a phenomenal job of making you feel special. You encounter something puzzling, you pursue it (don’t give up!), you have a flash of insight, execute it, and then trumpet: “I HAVE A KEY!!!” Whether you solved it solo or with teamwork, you’ve accomplished something real.

Well-designed escape rooms feature a variety of puzzle types, so the game rewards all sorts of behaviors and personality types. Immersive theatre tends to reward one kind of personality, whether that’s the empath (Third Rail), or the hyper-aggressive weasel (Punchdrunk). The things I do and become range more in escape rooms.

Escape rooms also deliver an individualized experience. Unless the puzzle flow is ferociously linear, people work on multiple puzzles at the same time. Like the best of immersive theatre, you’ll want to froth afterwards—to share a drink with your friends and swap stories of your individual experiences.

Rule #2 is actually the criterion that is hardest for theatre productions to meet, and escape rooms freakin’ nail this. Immersive theatre creators, pay attention. Think about game mechanics. Dare to make your audience more active. Rule #2 is what makes you both popular.

Rule #1: The world surrounds the audience, or “Immersion”

Escape rooms are certainly 360-degree spaces that you can touch, but I need a bit more world building than just “being in a room” to feel truly transported.

Most escape rooms feel like spaces designed for a game more than inhabited places. They often look a little empty. And there are good reasons for that…

1. Less stuff minimizes red herrings and streamlines puzzling.

2. Owners tend to be puzzle people, rather than set designers, artists, or theatre artists. Immersion, whether DIY or contracted out, costs money. Some owners also consider it non-essential, “nice to have,” but secondary to the puzzles. (For deep immersion, you need to design sets, puzzles, and story all at the same time).

3. People break things in escape rooms (especially in the ones that boast about their level of difficulty. Hard => frustration => destruction). The more stuff there is, the more stuff there is to break, which again, costs money.

There’s a thing in the business called “red herrings”—something that looks like a clue but isn’t. They can vary in degrees of evil from a book with pages circled in it in a room with number locks (most evil) to a chair with a lot number on the bottom (negligent) to a piece of art on the wall (fairly innocent). None of these are the clues you’re looking for. But how should you know better?

Most escape room designers recognize that red herrings frustrate players and are not cool. And no matter what you do, players will always make up their own red herrings inside your room. So to streamline the puzzle experience, designers leave in only what’s relevant and kick out anything that’s extra. This leads to a sparse room that feels designed for a game, because it is.

Real spaces have stuff. LOADS OF IT. Imagine the escape room that would happen in your average American bathroom. It’d take 30 minutes just to correctly identify the puzzle. Compare it also to the deep décor in the McKittrick. How long would it take to find and solve just one puzzle in the fifth-floor hair-lock filing room? Because it’s not a game, but an experience, immersive theatre can go all out on décor in a way an escape room never can.

I recently played a game that went for immersive décor. In his introduction, the game master requested that we handle “the museum room” very gently. I’m sure this rule was instated retroactively, when they realized that the room as-designed couldn’t withstand the beating that escape rooms take. And even with the rule, the game master had to tell my team twice to get out of that room and stop searching in there. There was a lot to look at. How were we supposed to know there was nothing more to find in that space? But it was a beautiful room, totally befitting the absent-character who inhabited the space.

In that escape room, the immersive environment came in conflict with the mechanics of the game. Which should win?

I stand guilty of a similar sin. I took an immersive-theatre-design approach for our tarot reading room at Madame Daphne’s—it hosts a density of details.

But I can only get away with it by explicitly telling players that you don’t have to remember anything in that room. And even with that rule, I still hear the occasional team talk at the start of the game about potential “clues” they found in the lobby. It’s a hard tightrope to walk.

But immersion goes beyond what you hang off the walls. There should be a deliberately-crafted logic to the space, evidence of human, or alien, or cat behavior that informs everything there. Nothing should be random—every item contributes to building the world.

The generic conventions of escape rooms make this exceptionally hard to do. We call it “escape room logic”—there are numbers on the back of these pillows, so let’s go put some iterations of these numbers into this lock that happens to be on this cupboard—wait, what? Who the hell lives in this apartment?!?

In a recent game I played at a high-quality company in the US, the immersion actually fooled me. I expected a device to work, like in Myst, and kept waiting for my team to do the thing that would inevitably give it power. Instead, I should have paid attention to what was sharpie-d on it and plugged it into a nearby lock. In a way, the absurd, not-a-thing-a-human-would-do escape rooms tropes stood out more in this game because the sets were so believable.

You have to jettison escape room logic for total immersion, and that isn’t easy to do. I predict that once the industry gets the décor thing figured out, this will be the next step. (For a good challenge to designers, read Scott Nicholson’s “Ask Why: Creating a Better Player Experience through Environmental Storytelling and Consistency in Escape Room Design“)

But even with all these hurdles, escape room creators are beginning to consider immersion an essential part of the experience, and I couldn’t agree more. Strange Bird Immersive has placed a bet that people want a unique experience much more than they want hard puzzles. We love puzzles, but we got into this business to deliver a potentially-transformative experience, with puzzles conceived as a means to that end. Every escape room advertises itself as a cinematic adventure in which you’re the star of a story. Shouldn’t the game itself make good on that promise? Good news is more and more companies are delivering on that promise every day, walking that tight-rope of deep immersion and clean gameplay.

rule #3: live performers telling a story

To be “theatre,” we need an actor. Some games use an in-room game-master to monitor and hint the players, but putting on a lab coat doesn’t make you an actor. There’s a difference between an in-character game master and an actor. Is the actor a pillar of the experience? Is there a character arc, and is this person advancing a story? Or could you replace the actor with cameras and a video screen and not have taken the soul out of the game?

Which brings us to story. Characters in theatre are there to progress a story. Story has a beginning, middle, and end—what’s happening changes. A scenario is not a story. I’m not certain where to draw the line, but “escape the zombie” doesn’t quite count. Granted, every team leaves an escape room with their story: “first we did X, which unlocked Y, which we paired with Z to get the key to Q, etc.” But immersive theatre delivers narratives more interesting than a list of actions taken. There needs to be more, a there there, whether that’s players uncovering a story from the past or a narrative journey that players experience for themselves. Real story in escape rooms is rare.

Because it’s hard! If the story is presented tangentially, the players will ignore it—the things must be solved! Integrating story into an escape room means making the solution to the puzzle require engagement with the story. You can’t solve it unless you pay attention to the story. That’s a damn high bar for your average escape room puzzle. I’m not sure even we achieve it.

I think an escape room is by its nature hostile to immersive theatre work. Everyone’s too frantic and focused on the puzzle in front of them to heed the actor, who is rarely the center of puzzle-attention. In the same way that people scan a letter to find “the tricky detail” instead of reading it, they tune out the actor until the actor’s “tricky detail” is needed. The actor is just another obstacle on the path to winning.

Despite these difficulties, I believe story is worth fighting for. Story is what can lift an entertaining night of puzzles into a transformative experience that unseats your soul. That is the aim of art, isn’t it?

Strange Bird decided back in 2015 that if we wanted to tell a story with actors, we had to do so outside of gameplay. Our actor moments function as cut-scenes and bookends: we offer a longer experience than the traditional 60 minutes of gaming, which frees us to deliver a complex narrative that doesn’t compete with the game for player attention (get a taste of the story in our new trailer). It’s not the wisest financial move—we can run far fewer games a day than our competitors—but it’s what the narrative needed, and I hope other companies try out a similar structure some day. It makes for a more complete experience.

But it is financially stupid.

room escape artist’s list

Lisa and David Spira over at Room Escape Artist are the juggernaut reviewers of escape rooms. They’ve played over 360 of them, and they’re also fans of immersive theatre.

I asked them for rooms they consider to be immersive theatre experiences as well, and here is their list of games that meet their criteria:

“1) Have actors; 2) Are escape rooms; 3) For whatever reason I think they capture the immersive theatery je ne sais quoi”

Note that this list is only for rooms they have played, so it’s not comprehensive, but it’s a great place to start! (Updated February 11, 2018)

ATLANTA

Al Capone’s Speakeasy (Review)

HOUSTON

The Man From Beyond (Review)

NEW YORK

Accomplice (Reviews)—multiple games

Paradiso: The Escape Test (Review)

Paradiso: The Memory Room (Review)

The Sanatorium (Review)

SPECIAL SHOUT-OUT: RED (Review)—”not an escape room by any real definition. It’s an immersive game.” While it shouldn’t be confused for an escape room, RED doesn’t have any peers in the realm of immersive-theatre-games, so I couldn’t leave it off this list.

LOS ANGELES AREA

The Basement (Review)

The Basement’s The Study (Review)

The Nest (Review) Not considered by its creators as an escape room, but features light escape room-style elements

Zoe (Review)

PORTLAND AREA (BEAVERTON, OREGON)

Madame Neptune’s Voodoo Curse (Review)

TORONTO, CANADA

Escape Casa Loma (Review)

THE NETHERLANDS

The Girl’s Room (Review), “no actors in this one, but the tech made it feel like there was one.”

The Vault (Review)

CLOSED

Club Drosselmeyer in Boston (Review), “which is one of the best examples of escape room / immersive theater intermingling.” A sequel is rumored for this winter…

A Pirate’s Tale in Orlando (Review)

Go PLAY!

Unless you’re in LA or NYC (the current hubs), you probably don’t have any immersive theatre within a full-day’s drive of where you live. But chances are you do live in a town with an escape room—or twenty! And even if it’s missing a narrative, even if it’s not striving for immersion, an escape room always delivers an active experience.

Strange Bird Immersive decided to launch with an escape room, because Houstonians had actually heard of them. It’s our foot in the door. Escape rooms offer a major opportunity for introducing immersive work to wider audiences, getting folks addicted nationwide to experiential entertainment. Yes, it’s seriously hard to meld the two genres together in a way that doesn’t frustrate players nor shortchanges the story, but it’s not impossible.

We have a lot to learn from each other. I hope immersive theatre starts experimenting more with gaming elements—a wider range of engagement. And I hope the escape room industry in its turn will pivot towards what immersive theatre does so well—a transportive experience that delivers immersion and story—actor or no actor.

The link to the Meisner Independent Activity exercise is inspired. I never thought of it like that, but I clearly need to. And it’s also how I was taught that activity divorced from specific mention of Meisner.