It’s the end of the gift-giving season, and I’d like to offer the kind of post that might spark some fireworks for creators in the new year.

Let’s define the word “scene.”

I’ve been thinking about this a lot. What’s the difference between a gripping scene and a scene that people tune out?

I think with The Man From Beyond, we wrote scenes based on instinct, without a firm definition of “what makes a scene.” A fair amount of what writers do I think is instinct based on osmosis from years consuming storytelling across all sorts of media.

To quote the artist-musician Brian Eno, intellect is often catching up with intuition.

But when you do have a firm definition and can stand back, do the intellectual check (not just the gut check), to see if you have written a scene, your work will achieve true consistency.

Basic definition

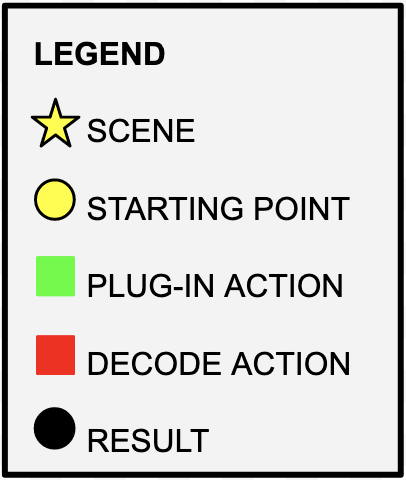

Merriam Webster: a scene is: “one of the subdivisions of a play,” but also potentially “the place of an occurrence or action,” as in “the scene of the crime.”

Oxford: a scene is “a part of a film, play or book in which the action happens in one place or is of one particular type.”

A scene is a discrete part of the continuous action of a story. It is often defined by a particular place, changing when the location changes, or when someone enters or exits. Something certainly is happening in a scene. Note that both of those definitions include a nice little word, “action.” Maybe begins to suggest movement.

But a two minute bit in which I make oatmeal is not really a scene, now, is it?

But what if… I’m signing a song to the morning sun, open the pantry to make my oatmeal, but discover that it’s gone, I forgot I ate it all yesterday. I break down sobbing on the kitchen tile floor because I fear I am beginning to lose my memory.

Now that’s a scene.

A scene is…

Change.

It’s that simple. The scene begins, your character expects one thing to happen, but then: SURPRISE! Something else happens instead.

If nothing changes in your scene, you have a wheels-spinning-in-place or slice-of-life bit that, unless you’re dedicated to some serious post-modern story-telling project, should be cut from the final edit. No one wants to watch me make oatmeal when it doesn’t at least overflow.

Put even more simply: you should never see a scene of someone knocking on the door and being cordially let inside.

I see this mistake a lot in all sorts of media: nothing changes by the end of the scene. Everything goes exactly as you expected, or worse, they TALK, and nothing happens. It’s boring, just like life. This mistake is being made at all levels of professionalism, beginners and Hollywood pros.

I prefer to call moments in which nothing changes “vignettes” rather than “scenes.” It’s a snapshot, a static moment, rather than an event. Vignettes are fine, you can make a whole show out of vignettes if you want, but events are more interesting.

Start looking for scenes as you consume your stories. Ask: did something change? Or did everything end just as it was when it started? You’ll find the scenes you enjoy the most involve change.

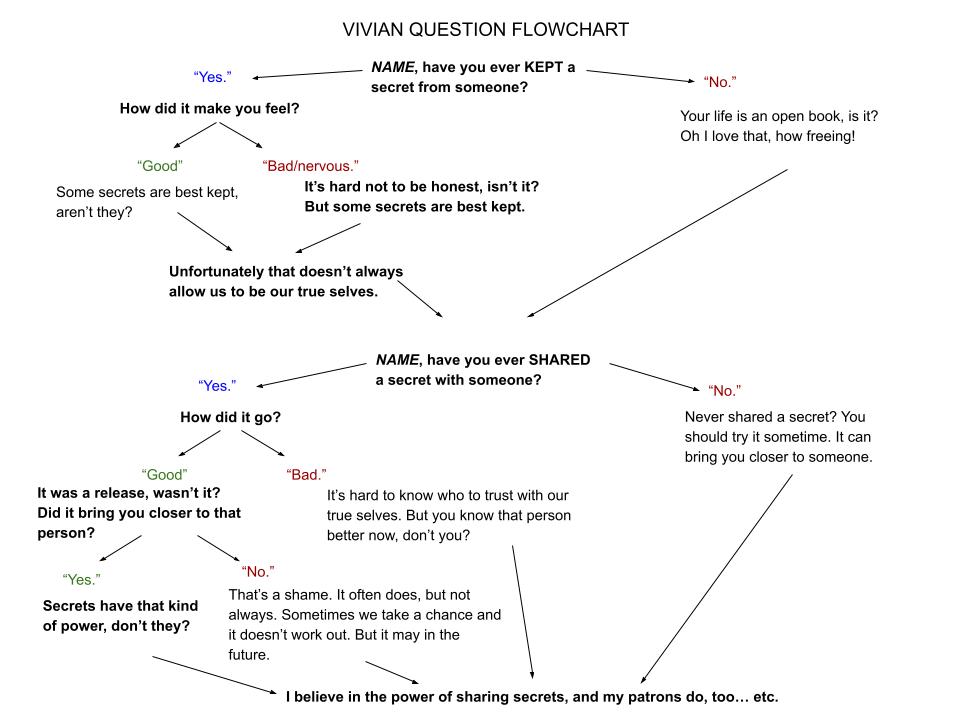

I sometimes like to say “a scene is surprise” because “surprise” is a bit more specific than “change.” Change is a little nebulous, but surprise is a more concrete box you can check. In a scene, someone needs to experience surprise. Something someone didn’t expect to happen, happens. In an immersive or in an escape room, the character can be surprised or your players can be surprised. Either one works! But you need to subvert expectations in every scene.

Thwart Your characters

Of course, it’s not enough to have a jack-in-the-box go off in your scene. The surprise has to mean something to someone in the scene.

Your characters need to want something, what is called motivation. The character enters the scene wanting something. By the end of the scene, the character either is thwarted in their desire, or undergoes a redirect—they see a new avenue for getting what they want that they now must consider. One or the other.

Only by the end of the entire story can the character get what they want. (Or not—up to you.)

So let’s say my characters (or players) need to stay hidden in an attic. Then they bump into an old jack-in-the box. And the enemy finds them! STAKES.

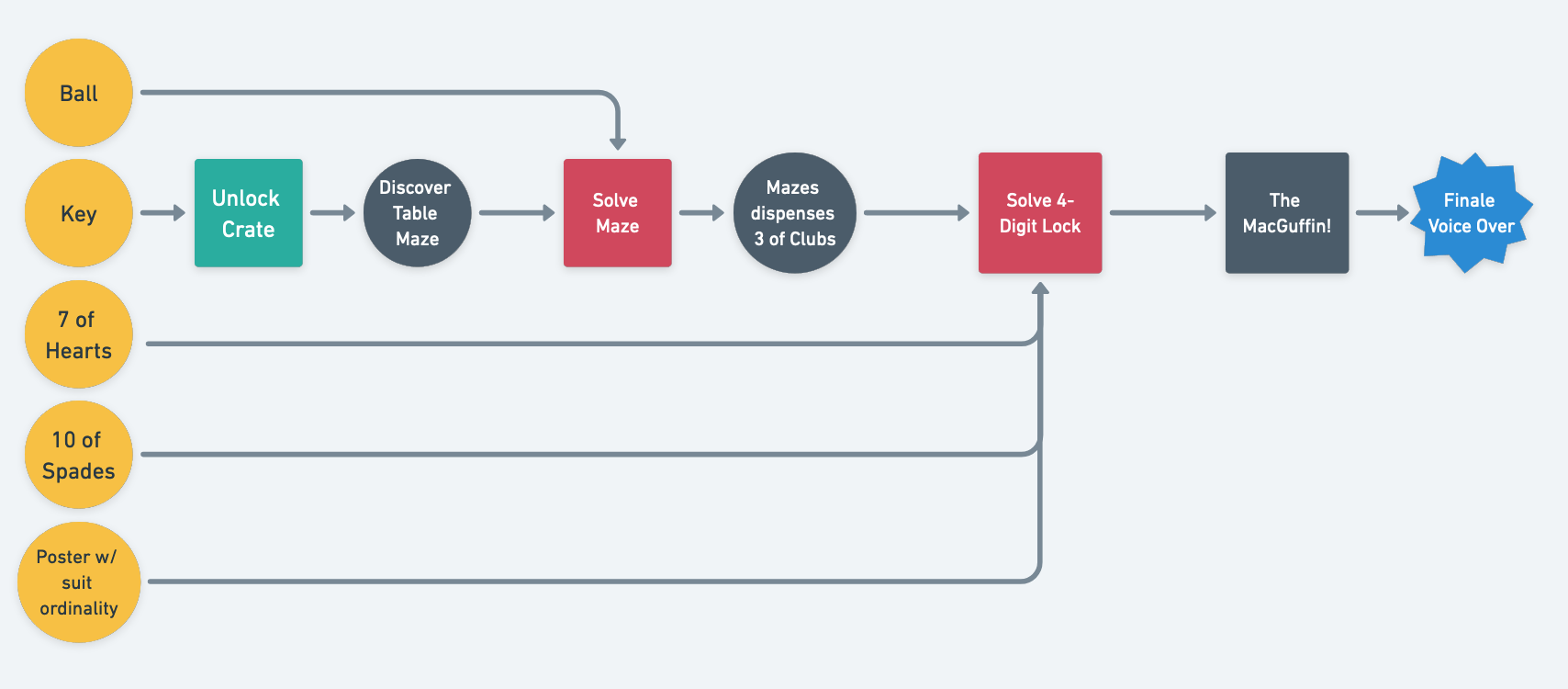

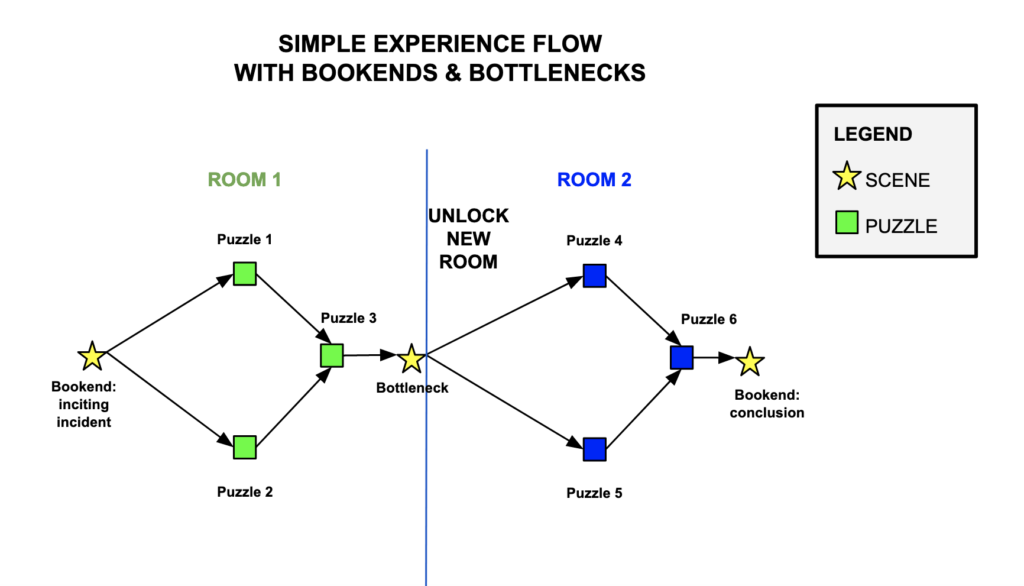

Scenes in Escape Rooms and Immersives

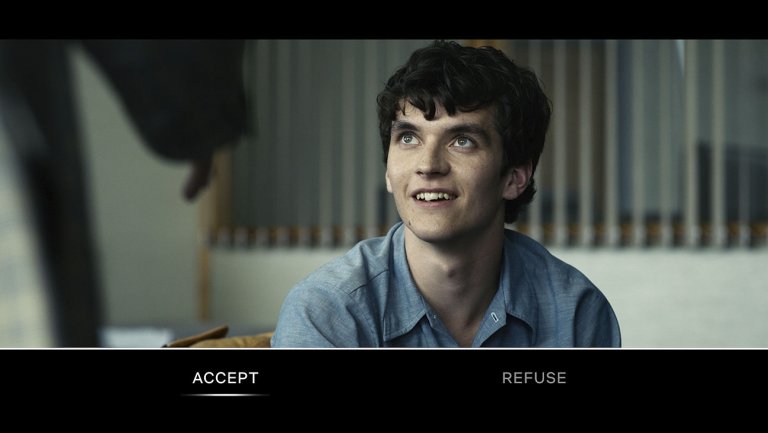

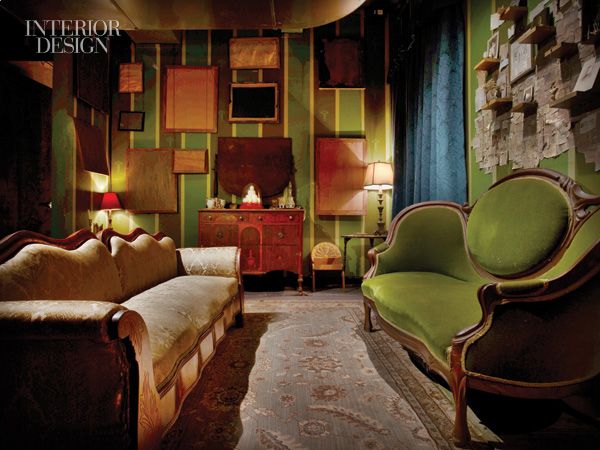

What makes escape rooms and immersive theatre great is they deliver embodied surprise. It’s more powerful than the flat surprise happening to characters on a screen. People love discovering new things for themselves, whether that’s what’s in a previously locked box or what’s behind a closed door. Design for surprise, always.

But surprise should come from more than just set and props. Characters can surprise players, too. You’ll use your non-playing characters best if they deliver unexpected things to the players. Remember that people are wayyyy more dynamic than sets.

And it can go the other way, too: players can surprise characters. Which is really exciting and totally not a thing that can happen in traditional theatre. As a performer, I love nothing more than when a player surprises me. As a writer, I create opportunities for the players to participate in the scene as the deliverer of surprise, the catalyst of change. It can be even more thrilling than “what’s behind that door.”

So if you have a video or voice over in your immersive, whether at the opening, closing, or in the middle, make sure it’s delivering surprise. If you have a live actor… oh, the possibilities! Actors love nothing more than delivering or receiving surprise. It’s really this little thing called drama.

But even if you have no non-playing characters in your world, you still have scenes with your players to write. Write them for movement.

What is story?

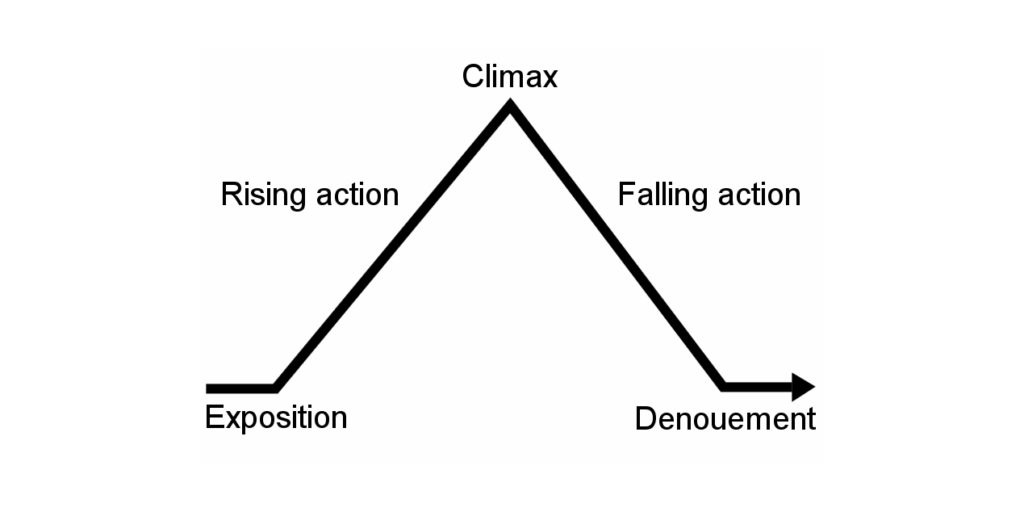

Story is scene writ-large. Something BIG needs to change in a story. If the world is the same when I leave as when I entered, what’s the point?

If you’ve played a lot of escape rooms or done a few immersive theatre pieces, you know a big change doesn’t always happen by the end. I’m not a fan of it. These are not the experiences that stay with me.

Recommended Reading

If you’re inspired by this post, treat yourself right now to Pulitzer Prize winner David Mamet’s absolute power-screed on writing drama. It’s a rant to the writing staff of The Unit. It’ll take you all of five minutes to read. He says it all better than I do—and with more expletives.

An excerpt (yes, it is in all caps): “IF THE SCENE BORES YOU WHEN YOU READ IT, REST ASSURED IT WILL BORE THE ACTORS, AND WILL, THEN, BORE THE AUDIENCE, AND WE’RE ALL GOING TO BE BACK IN THE BREADLINE.”

Cameron and I enjoy reading this out loud every few months.

If you’re up for deeper dives…

In my self-guided tour, I found myself where many writers end up: at the feet of Robert McKee.

Robert McKee’s book Story has informed a great deal of my thinking, as has his equally excellent Dialogue. Heck, while you’re there, dive into Character, too.

To whet your appetite…

From Story: “Scene is unified around desire, action, conflict, and change.”

“Big helpings of static exposition choke interest.” (Dialogue)

“When scenes fail, the fault is rarely in the words; the solution will be found deep within event and character design. Dialogue problems are story problems.” (Dialogue)

“All stories dramatize the human struggle to move life from chaos to order, from imbalance to equilibrium.” (Dialogue)

“Plot is character; character is plot.” (Character)

There’s also the screenwriter’s book Save the Cat by Blake Snyder, which (in)famously offers a beat sheet, outlining the minute by minute moments of a successful film.

From Save the Cat: “Danger must be present danger. Stakes must be stakes for people we care about.”

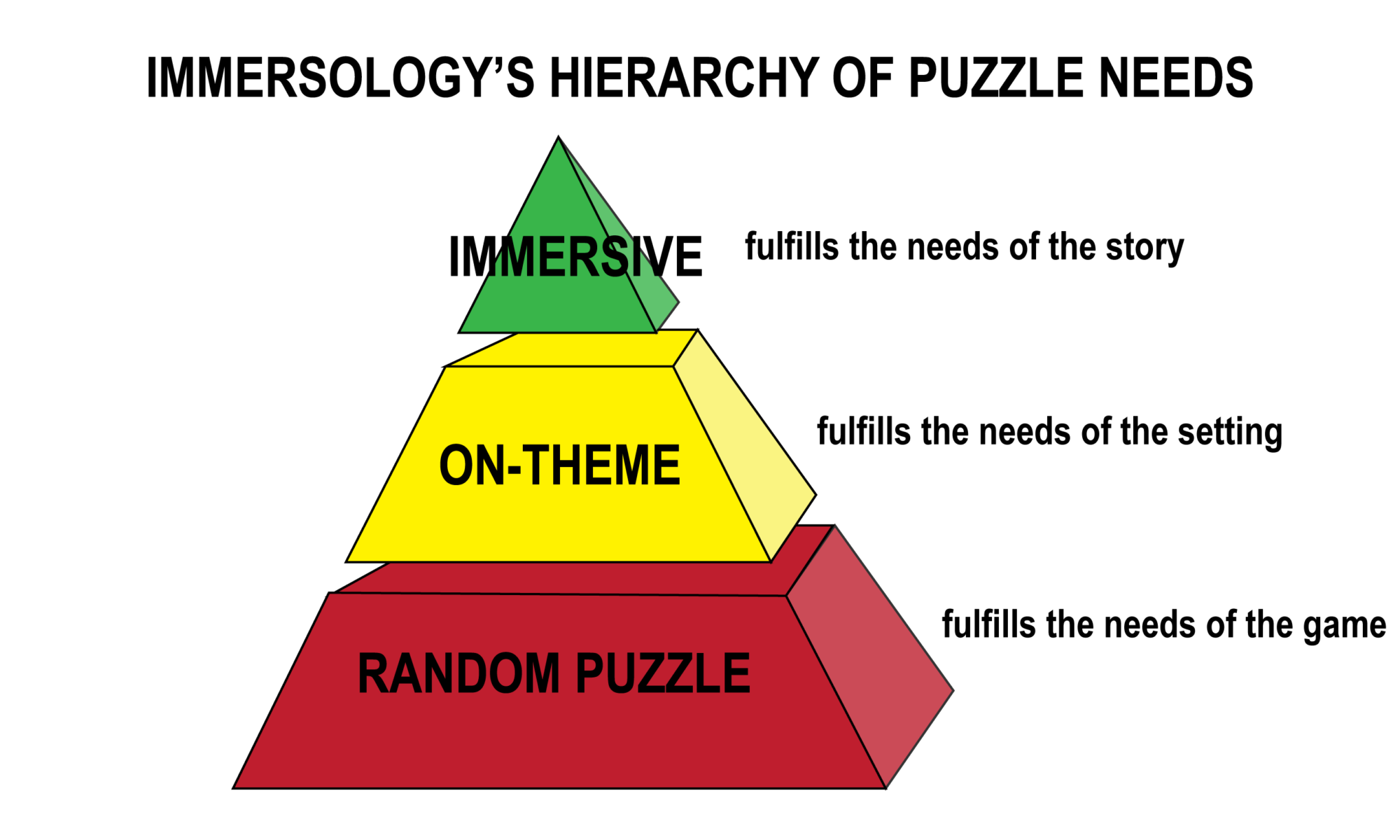

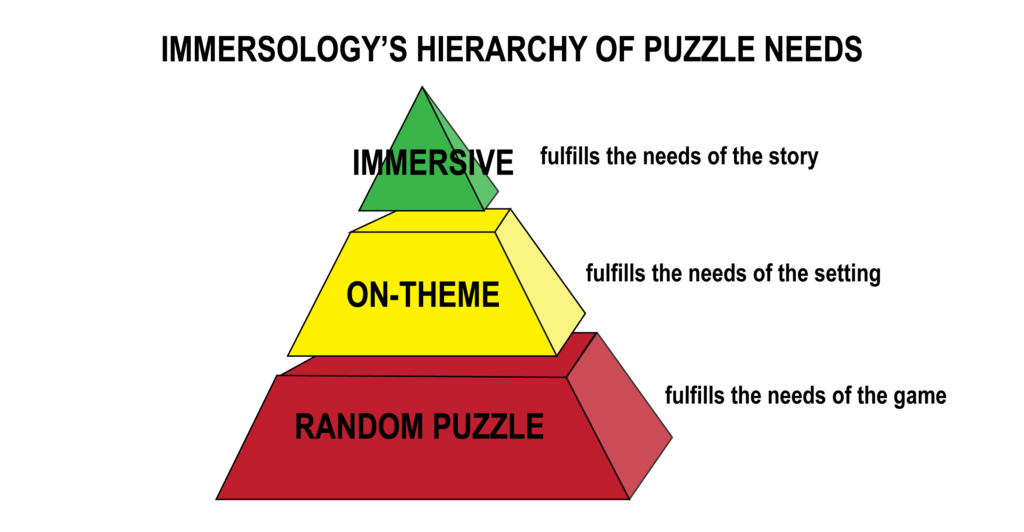

If you’re an immersive creator, you will want to adapt this advice for our medium, which adds the twist of turning our audience into characters we need to write for. To quote David Spira of Room Escape Artist, “Immersive experiences are about living the moment: not showing and certainly not telling,” which challenges us to develop a new story-telling approach. That being said, I feel strongly we are closer to screen (images) than stage (words), so keep that in mind.

Go on now. Surprise me.