EDIT: after publishing this article, I learned that some might call “immersive puzzles” diegetic, some might call them mimetic, and in general, “diegesis versus mimesis” is a hot mess, exacerbated when film decided to use diegetic to mean its opposite (read this great piece from Errol Elumir, published after this article). To sidestep this problem, I’m proposing that we call the concept “immersive puzzles,” as that clearly expresses both that extra level of sense and the ultimate goal to immerse the players in the world. In other words, I’m stubbornly refusing to edit this post.

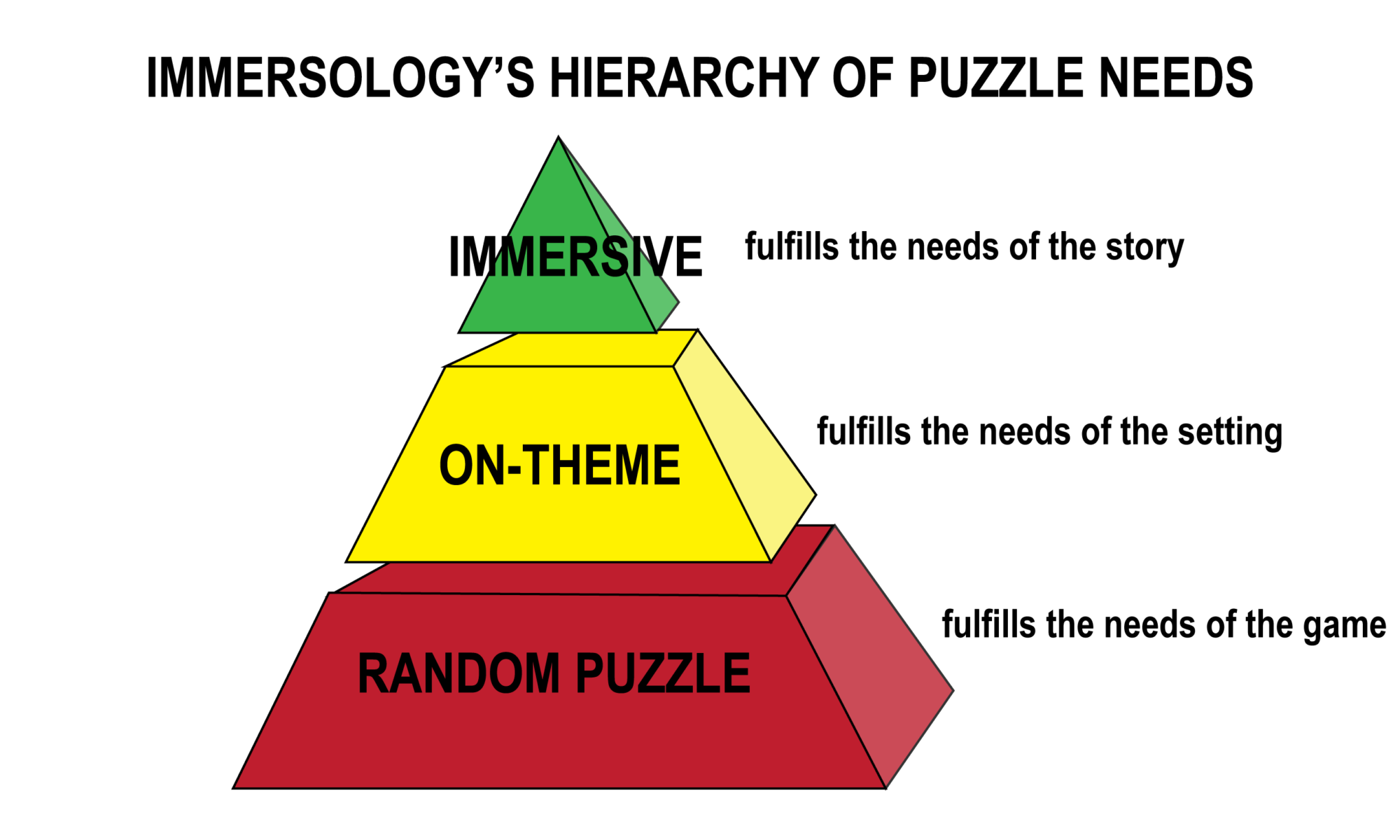

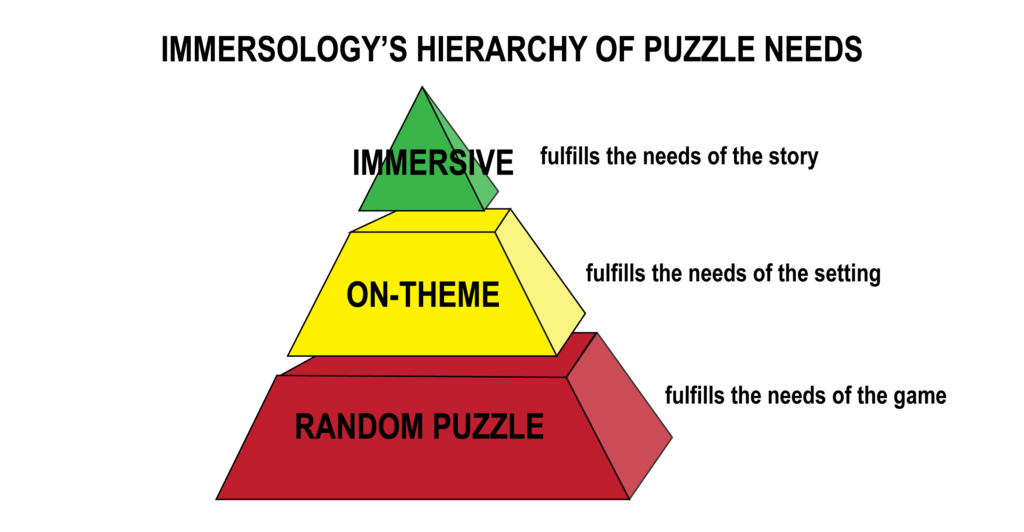

In the escape room community, you often hear about puzzles being on-theme or not. (Important note: “theme” in escape room lingo means time-and-place, like a WWII submarine, not “theme” in the literary sense of ultimate message, like “war is hell”). Puzzles deemed “not on-theme” don’t blend with the game’s setting—”Shame on you, rando-puzzle!” As escape rooms have grown in sophistication, I’m hearing this complaint less and less. More and more rooms seem to be presenting challenges that are “on-theme.” And yet, I still find myself playing games where I feel like the puzzles lacked a shred of sense.But I’m judging not by a binary. I’d like to propose a third category that goes beyond “on-theme”: is the puzzle immersive? An immersive prop or puzzle dives me deeper into the plot, character, or world. In short, when you step back to look at it, it makes sense. When it’s immersive, it isn’t just decoration; it’s revelation. I can clearly see the human hand that set up this challenge or created this thing—and the events that have brought me to this place to solve it.

Basically I’m proposing we permanently enshrine Nicholson’s “Ask Why” paper with a new tier for judging puzzle quality. (If you haven’t already, read it.)

CASE STUDY

Let’s say you’re in that World War II submarine.

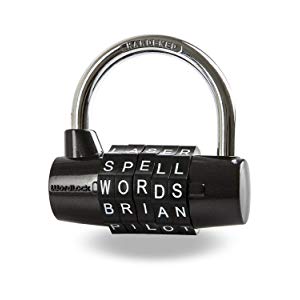

Random puzzle: there’s a steel-ball tilt-maze that I need to navigate to get the ball through a hole that completes a circuit, turns on a blacklight, and reveals a four-digit combination that I then plug into a lock. Cool. I confess I’m a maze-hogger, and I’ve done tilt-mazes in games before, they’re pretty fun! But this is clearly not a thing that has ever happened on a submarine—WWII or not. Why even bother building an immersive set? No matter how fun it is, this is not a cinematic engagement.

On-theme puzzle: the captain’s jacket has morse code symbols on it, that I then need to punch out on a morse telegraph key that then magically throws open the door to his cabin. NEAT! That’s nautical! But wait…why does the captain wear morse code on his jacket? If it’s a password he wants kept secret, why would he flaunt it? Also how does the right morse code lead to a door magically opening? Is this submarine haunted? Why would the captain leave his uniform behind in the first place? This feels…artificial.

Immersive puzzle: your team of soldiers has stumbled upon a scuttled German U-boat that can still be salvaged. You first need to close all the valves that have been opened and disable the demolition charges set to go off. Once you’ve saved the submarine, you break into the captain’s quarters and find a coded message from the day it was abandoned. The codebook has different codes by day, so you use a calendar from a shipman’s locker to decipher the right day, then decipher the code, then translate it using the German-English dictionary left behind (hey, the Captain needed it, too!), and win the game by predicting their next coordinated attack. (Inspired by German U-505, for the curious).

Note how the immersive puzzle required me to make up a scenario, whereas the other two didn’t engage a scenario at all.

Any given challenge has three stages: puzzle, solution, and what it yields. An immersive challenge is not only a puzzle that makes sense in the world, but its solution and what it yields are also logical. Solutions shouldn’t just come from something random in the space (like an hour’s sign being the password). The solution instead should come from understanding the person who set the password. And if you’re using magical tech for reveals, be sure to have a supernatural or otherwise very clever character behind it all.

Note how essential the character becomes to the immersive challenge.

It’s a high bar.

Just what are escape rooms selling?

In the early years of escape rooms, designers didn’t make puzzles out to be anything other than a good puzzle. Rooms were rooms, puzzles were puzzles, and all you had to do as a designer is make a good flow of puzzles. This sort of game put a lot of emphasis on the locked door for player motivation—it was the only thing that could really qualify as “story.” But fairly quickly, owners shifted away from selling pure puzzle games (let’s be honest, it sounds a bit nerdy!), and instead started marketing their escape rooms as cinematic adventures. Nowadays designers have to pick a setting and then sell a story.

I should know better by now, but I can’t help it—I am so easily seduced by those three-sentence scenarios on escape room websites. They set my imagination on fire. I can’t wait to bring the story to completion. And I know I’m not the only one. We’re a story-telling species. It’s well-known that casual players are primarily motivated by a room’s theme: does it sound awesome or not?

Trouble is, while they may deliver on décor, escape rooms drop the story-telling past the marketing stage. Game masters may read that blurb to you before leaving you in the room, but then it and all the characters mentioned disappear from the game. Talk about bait-and-switch: you sold me an adventure, and then you hand me puzzles in a decorated room. Are on-theme puzzles really making that material a difference, when the heart of what you sold me is missing?

Strange Bird Immersive is gambling hard that the industry will eventually wake up and start delivering what we’re selling. And that’s a cohesive experience that dives players deeper into an imaginary world.

How to achieve immersive props and puzzle

Always begin with your big picture: what’s the story, and who are your characters? And by characters, no, I don’t mean the players (see: When You’re the Star on the importance of non-player characters). I mean the people who inhabit the space and/or the people who built the space for the players to engage with.

There is no such thing as a room without an author. So who’s behind yours?

My rule of thumb for writing (and acting) is, “Is that a thing a human would do?” A simple question, but one that most designers don’t think to ask. If the answer to this question is “No,” then I am left in an artificial game, constantly aware that a game master is monitoring my progress in this office-suite-turned-submarine, battling not the antagonist in a story but a bizarre game designer, who literally could have made the answer just about anything.

Giving each puzzle a human logic not only enhances my immersion, it also makes the puzzle easier. And yes, that’s a good thing! Players who win a game come back for more—seriously, Escape Games Canada measured it. Grounding everything in human logic means I am more likely to look for solutions that make sense over something random, which delivers pleasure over frustration. Players want to say “Aha!” not “WTF?” When you need to deliver a hint, you want players to exclaim, “Of course! Why didn’t we see that before?” not, “Wait—say that again?”

I admit that escape rooms have quite the acrobatic feat to pull off if they really want to answer WHY. Why would someone place a web of interconnected challenges in this particular location for someone to solve in exactly 60 minutes? This is typically not a thing a human would do to begin with. So we’re on the hunt for exceptional humans. It’s easiest to say “a serial killer is testing you,” or “there’s a secretive magician, inventor, or spy who left behind these weird things for you to decode,” or (my favorite) “there’s a supernatural power at work here that needs you to do its will”—there’s a reason why these themes are so popular. But there are other explanations out there. Get creative. Just because it’s hard doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing.

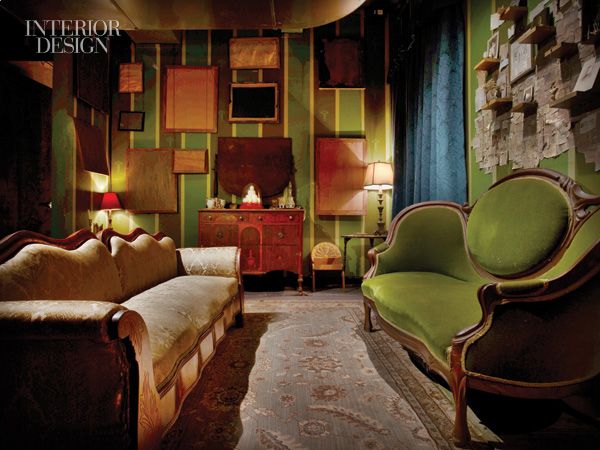

Like a skilled magician, who uses multiple techniques to perform the same trick, you can have multiple answers to why. Some things in The Man From Beyond are Madame Daphne’s, some things are stolen from Daphne, some things are historical and Daphne knows about them, some things she’s never discovered before but have been there all along, and some things have been brought back into being—we have five different reasons why something is in the space. And that lends our séance parlor layers of richness for the players to discover.

Once you have your characters and your story, you can start getting into the details that enrich a puzzle. In design meetings, we start first with the story, then devise a puzzle, and then find a way to make its connection to the story clear. Sometimes it’s as simple as good set dressing. Instance: we needed an approachable on-ramp puzzle to begin the game, so we devised an unusual maze. Not exactly the most compelling story-telling device—admittedly mazes are hardly “Houdini-themed”—so we crafted a jewelry box and added a gift tag on it from Houdini to his mother. Boom. Immersive. Even better: that tag may be a clue to something else…

Immersive props in immersive theatre

Not designing an escape room? Guess what: the same principle applies to props and décor in immersive theatre. Sure, you can stuff a room with something shocking all day long, but that’s flat and forgettable. It won’t mean anything to the guest who discovers it. Build that connective tissue! Ask why! Reward your audiences for paying attention! If they’re snooping through drawers and find something, it should be exactly like a clue in an escape room: another piece of the story. You want them to say “Aha!” and share the story-connection they discovered with friends afterwards.

Case study: in Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More the Macduffs’ apartment features multiple kid rooms, including one with creepy baby dolls hanging from the ceiling around an empty crib. But the creepy baby dolls aren’t just creepy. They’re a clue. Look around, what else do you see? Or don’t see? Where, oh, where are the children? And it seems the mother is pregnant again. Put these clues together, and you’ll see new nuances in their pas de deux.

That’s the bar, my friends. Let’s jump it!