As I’ve claimed before, “Rule #2: The audience is active” is the game-changer in the genre. Theatre is good fun, I’m usually laughing or learning in the dark, but immersive theatre sees me. It gives me opportunities to explore myself in new contexts, face new challenges, and come out on the other side a little different for the experience. I did not just witness the story, I built a relationship with it. I lived it.

It’s amazing when a gorgeous set is all around you, and perhaps you can even smell the meat pies, but things don’t get really interesting until you’re invited to make those pies yourself. Or perhaps, when you have to decide if you’ll help Sweeney Todd enact his revenge or not.

That, my friends, requires a new kind of writing, a new kind of performing, and a new kind of audience. It’s theatre that mirrors the imaginative play of childhood, except with way higher production values. This is how theatre can (finally!) meaningfully differentiate itself from Hollywood.

But not all activity is created equal.

A big difference among immersive theatre productions is how the piece engages you, and you often don’t know what you’ll be doing until you’re inside. Sometimes characters will float in and out of awareness that you’re there, some will build relationships with you that reward commitment, while yet others will directly ask you for aid. Sometimes even, you get to be the protagonist, and the actors buoy your story, functioning more like NPCs (non-playing characters). Different structures invite different activities.

For me, I don’t like to call it immersive theatre unless there’s sustained audience engagement. But once a production passes that initial hurdle from passive to active mode, there’s a lot of colorful territory to explore.

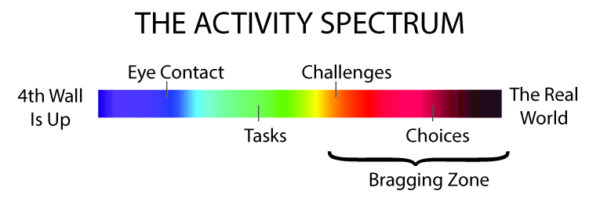

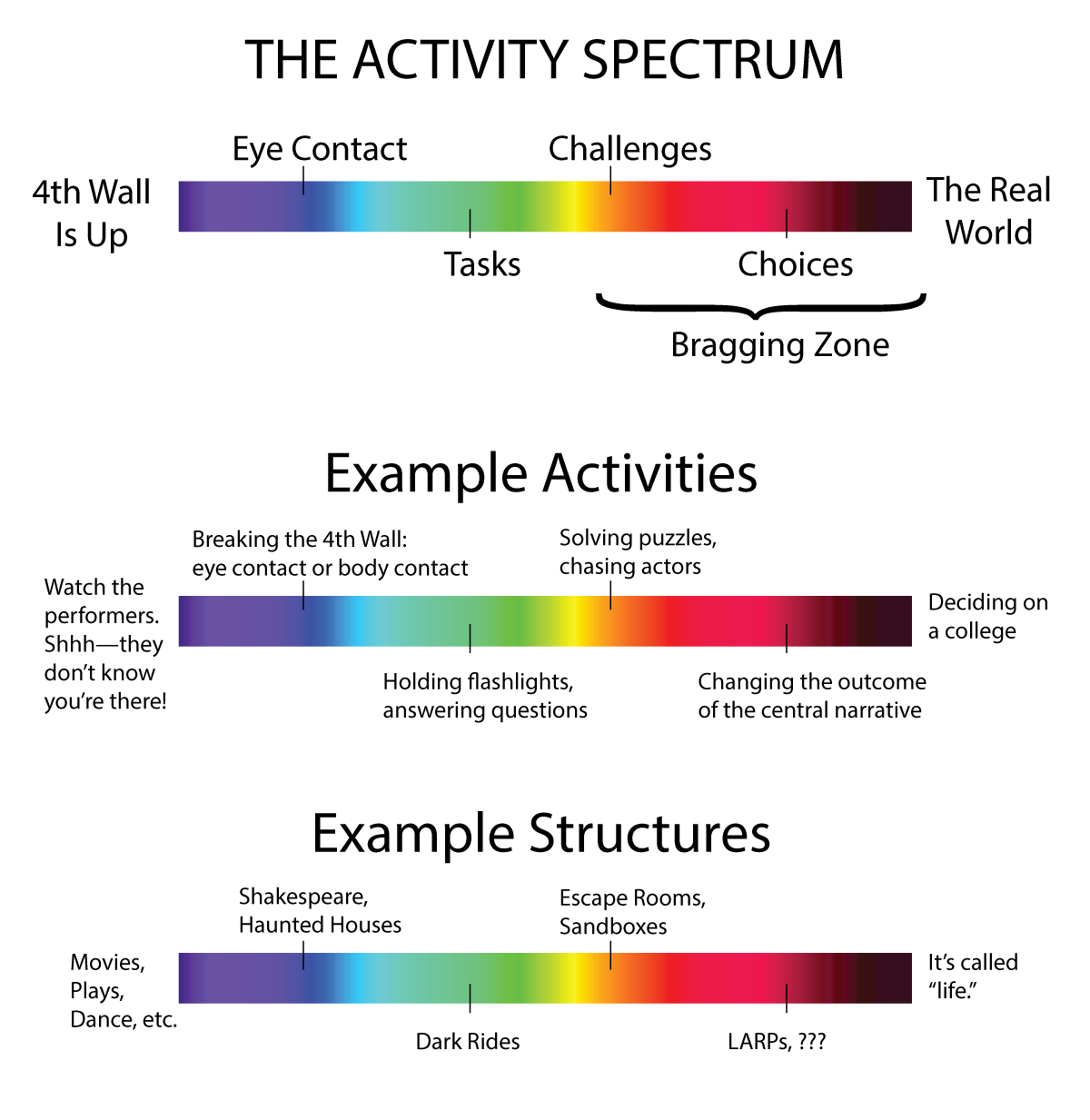

the activity spectrum

Because I have a strange fetish for the codification of qualitative stuff, I’ve categorized the range of activities common in immersive theatre into a spectrum.

Note that being on the left side of things does not make the production any less awesome than shows in the red zone. This is not a quality spectrum. Nor does a structure being on the right side guarantee that it will include the other forms of activity to its left. You can have a sandbox where characters never make eye contact with you, for example.

As you move left to right, you can expect to do things more like you do in real life. Presence turns to activity turns to agency. I consider these 3 very distinct stages. The first knows you’re there; it’s the start of a relationship. The second employs you but doesn’t make much distinction between one warm body and the next. The “tasks” tend to be easy, and if you fail at the “task,” there are no consequences. The third means you—yes, you! the particular you—can make a difference.

activity IS NOT AGENCY

To have true agency requires altering the story, whether that’s your story or the central story of the characters. “Challenges” lead to alterations in what you experience and typically present as binary: win/lose, pass/fail, do/do not. It’s up to you. “Choices,” on the other hand, have a deeper impact and influence the headlining story, affecting change that goes beyond “I saw this” or “I unlocked that.” The characters and/or other participants are affected. Choices are not necessarily binary, but can be.

Example: Completing a quest falls under “challenge,” but if completing it then alters the fate of a character, it moves into the zone of “choice.”

Escape rooms and sandboxes usually don’t go beyond the “challenge” stage. There aren’t many examples of “choice” immersives, and I can’t think of any common structures but LARPs (which may or may not be immersive theatre). There’s a lot of territory to explore in the red zone, but it poses many challenges—how do you structure an evening’s experience for multiple participants that allows each to exercise meaningful choice without ruining the show for the others? Perhaps a many-branched one-on-one train? And is that economically feasible?

bragging zone

I’ve identified the warmer area to the right as “the bragging zone.” While you can certainly tell the story of what you saw in a dark ride over drinks, you cannot claim to have earned it. In my first viewing of Then She Fell, I received the Alice letter-quest. While I was thrilled by what happened on that track, I could not brag about it afterwards—what happened to me was pure luck. I was navigated to it. I couldn’t own it.

But I can brag about puzzles that I solved or completing “the Malcolm Marathon” (he has a fondness for the fourth and first floors). Shows that enter “the bragging zone” mean you get to exercise your specialness.

Some people crave shows in the bragging zone: it engages more of themselves, and they leave with a more satisfying experience.

And yet others may want a little less engagement, a little less challenge, and a little more guarantee. Less choice means you’re free to focus on other things, like connecting with the performer in front of you, exploring where you happen to be, or piecing together the story. You won’t get a bad show because you can’t make poor choices. I get the sense that about 95% of people who visit Sleep No More come out dazed and confused, whereas Then She Fell guarantees every participant a quality experience.

And besides, don’t you sometimes want a break from the existential avalanche of never-ending choice that we call life?

Some days, I really wish I were on rails….

for story’s sake

Choose your activity wisely. The story of Sweet & Lucky would have been disastrous as a sandbox; gamification would do it a disservice. And yet its quiet invitation to do a task or two moved me no doubt more than if I had experienced it as a proscenium show. It’s at home exactly where it is.

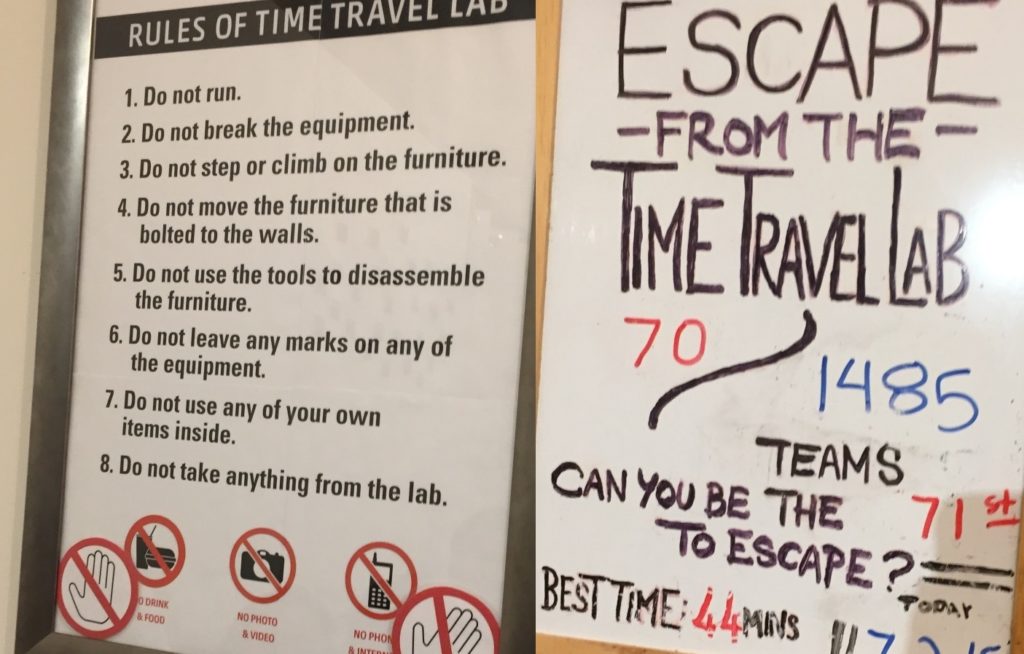

In our turn, take the escape room out of The Man From Beyond, and you have to re-conceive pretty much everything about it, to the point that it would be unrecognizable. The player experience is its foundation.

So before you jump on the immersive theatre bandwagon, consider the story you want to tell. What impact will different modes of audience engagement have on your story? Why is the audience there? Why invite them to do anything at all? What happens when audiences act more like friends? Or like players? I don’t want to be doing something just for doing’s sake—you need to go somewhere with it. Invest my activity with meaning. Then we’ll be really going places.