Dedicated to my sister who wanted me to explore the recurrence of the word gift in this blog, and my father, who told me over the phone to write this theory down!

With the close of the gift-giving season, I’ve been reflecting about the greatest gift I’ve ever received. Immersive theatre gave me something, something extraordinary, that goes beyond creative purpose and a career in the arts (both tremendous gifts). It gave me myself.

By which I do not mean I “discovered my true self.” We are always talking as if the truth is buried, and if we just have the right archeological tools mixed with the right tenacity (or the right therapist), we can uncover the True Self. The True Self has always been there, since birth, or at least since childhood, and it is our lifelong task to Know Thyself.

That is not what I mean. I mean that immersive theatre taught me that my identity is fluid, able to flex to given circumstances. It taught me that the “I” I call myself is much more expansive than I ever imagined.

Western notions of fixed identity

I cannot lay claim to intimate knowledge of Eastern traditions, but in the Western culture I consume, we think in terms of the True Self. Whether at birth or in the crucible of childhood, we supposedly solidify our identity early—and do not deviate from it. Children may learn and play, but adults are certainly set. Think about stories from your childhood that your mother likes to tell, and how they bespeak your present-day personality, crystal-clear even at a tender age. Adults are simply not expected to change much—that’s why marriages can supposedly work.

We take quizzes online to uncover the True Self, want to know which Hogwarts house we’d be sorted into, exchange our Myers-Briggs personality types with friends, so we can better understand each other. I even buy into the Five Love Languages thing. Mine are, surprise-surprise, determined by the love languages my parents expressed to me as a child.

There are probably kernels of truth in this theory of the self, but like most theories, we’ve taken it way too far.

For one, it’s overwhelmingly fatalistic. There’s not much room for free will here. You chose your career because of who you are. You chose your partner because of who you are. You have kids because you couldn’t choose otherwise—it’s who you are. When really, aren’t we just making it all up as we go along?

Someone very dear to me once transitioned from introvert to extrovert. Verifiable Myers-Briggs reversal and everything. Everyone was shocked. We didn’t think a change like that was possible. Suddenly we were dealing with a whole new person, with different desires and needs.

But this shouldn’t be shocking. People change—yes, even as adults. Our identity is not ordained or gifted to us by a Creator. We craft our own identities on a daily basis, in our situations and our choices within them. I call this “the situated self.”

IDENTITY as what you do

At those awful, theoretical cocktail parties where strangers for some reason gather together, we ask and anticipate one simple question: “What do you do?”

That’s a very interesting question. It suggests that identity comes from doing, from the actions we take. But that’s not really what we’re asking. We really mean, “What’s your job?”—a more boring question. The answer to that question supposedly encapsulates identity, gives the querent a succinct portrait of the stranger. Additional follow-up questions include, “Are you married? What does your partner do? Do you have any kids?” And maybe, if you’re lucky, we get to, “What do you do for fun?” These questions cover how you spend your time. They get to “the point” fairly quickly. What role do you play?

Your life situation molds your identity. Being and doing are intertwined—that I agree with. We experience existential crisis whenever we lose a job, divorce, etc., in part because our identity is tied up in our situation. The situation is changed, and so identity must change. Now that most people don’t stay with one job for 30 years, we’re beginning to open up to the notion that people can indeed do many things and so can be many things.

IMMERSIVE Theatre’s NOTION OF FLUID IDENTITY

In traditional theatre, the audience does nothing. They are not active, they are not present to the performers. It is rare for audiences to leave traditional theatre with an expanded sense of self. That’s not what it’s designed to do.

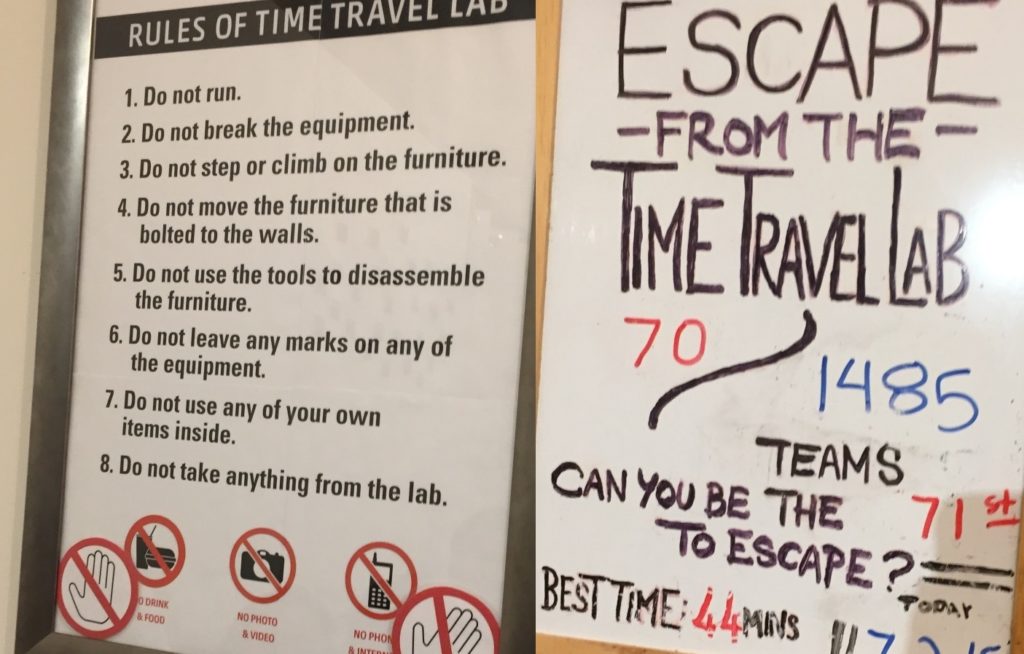

Enter an immersive theatre piece or an escape room, and you—body and all—find yourself in a radically different situation, a place and circumstance you’ve never encountered before or dreamed possible. Whether you’re cast in a specific role as an Egyptian archeologist or just given a task to perform, you are role-playing. You’re doing new things and so try on a new identity.

Yes, it’s make-believe. But that doesn’t make it any less real.

Humans are ultimately conservative. We like life to be predictable, each day to follow a structure similar to the last. We don’t like shifting situations, we don’t want to change our identity. No one would ever elect to change careers every year. But for us to do out-of-the-ordinary things requires encountering an inciting event from which we must take action. The old way of doing things just won’t work anymore in the new circumstances. Something must be done, and we must step up to the plate.

That, my friends, is participating in a story. Stories require conflict, but we eschew conflict in life. Immersive entertainment creates a safe space for us to encounter an inciting event and so take extraordinary action and become extraordinary people. Nothing is at risk here, but the reward is very real.

In escape rooms and immersive theatre, I have: lied to an Alzheimer’s patient, embarrassed a naked man when his lover asked me to, drunk glitter Champagne, stepped on a friend’s foot without even noticing, pushed strangers out of my way, french-kissed a stranger, stacked a deck in a casino, reunited lovers, summoned a ghost, sung to whales, translated binary, kept secrets, squeezed through cell bars, jumped through a window, flown up and down four stories of stairs as fast as the man I was following.

This is me. These are actions I am capable of—in the right situation. I carry all of this knowledge with me now. And sometimes I like to fly up stairs in parking garages, just to check my current capabilities.

Some of these actions I’m proud of, some I’m ashamed of, all of it I find surprising. Radical departures from my usual narrative of “who I am.” It’s empowering. And it’s in my body as a true memory—I was there. This is what I did.

This is the gift of immersive theatre: to call an audience to action inside of imaginary circumstances. It awakes us from our slumbering adult selves and invites us to play, to explore new identities, like children or actors do, and potentially, to take a new identity home. Talk about a souvenir.

Quality immersive theatre transports the audience into an easy-to-believe world, but falls short of requiring them to lead the story, as children or larpers do so easily, so un-self-consciously. That’s a good thing. It makes this kind of play accessible. The circumstance is all there for you. All you have to do is act. Go on, try on somebody else tonight. This could be you!

And it is you. When an immersive experience is well-designed, I leave with a strong sense that I can be anyone, do anything. I can choose my identity.

And that’s one hell of a gift.